Response in whole-brain models

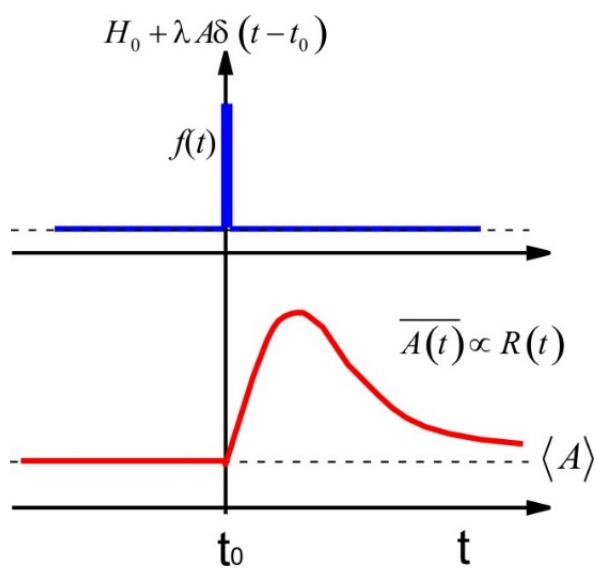

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem (FDT) is a fundamental principle originally formulated for systems at thermal equilibrium. It provides a direct relationship between the spontaneous fluctuations in a system and its linear response to external perturbations. This canonical form of the FDT allows one to predict how a system will respond to a small stimulus simply by measuring its internal fluctuations, reflecting the deep connection between equilibrium statistical mechanics and dynamical response theory. Recent studies suggest that deviations from the canonical FDT can serve as valuable indicators of how far a system operates from thermal equilibrium, opening new avenues for understanding complex biological systems such as the brain.

However, the classical equilibrium FDT is limited in scope, as many biological systems, including the brain, are inherently out of equilibrium. To address this, more general formulations of the FDT have been developed, which do not require thermal equilibrium but still connect response functions to the underlying stochastic dynamics for linear perturbations around stable fixed points. These generalized fluctuation-dissipation relations extend the theoretical framework to encompass a broader class of systems described by coupled Langevin equations with Gaussian multivariate distributions at stationarity. While these generalized theorems are less powerful in that the correlator functions cannot be fully reconstructed from response alone, they are considerably more robust and applicable to realistic models of neuronal activity.

In practical terms, this generalized FDT framework enables researchers to infer the response properties of a system purely from observational data, without requiring detailed knowledge of the microscopic model. For whole-brain dynamics, this means that one can analyze the spontaneous activity correlations across different brain regions to predict how these regions will respond to small external stimuli. Such predictions are invaluable for identifying brain areas that are more sensitive or susceptible to perturbations, and for characterizing the functional form of these responses.

In practical terms, this generalized FDT framework enables researchers to infer the response properties of a system purely from observational data, without requiring detailed knowledge of the microscopic model. For whole-brain dynamics, this means that one can analyze the spontaneous activity correlations across different brain regions to predict how these regions will respond to small external stimuli. Such predictions are invaluable for identifying brain areas that are more sensitive or susceptible to perturbations, and for characterizing the functional form of these responses.

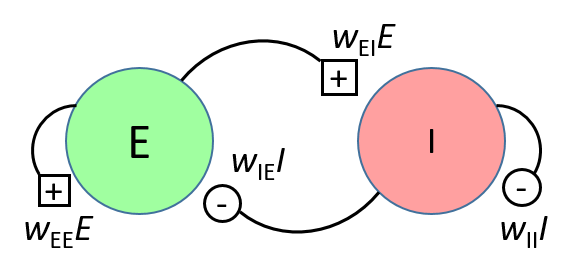

Our focus is on the linear response of a network consisting of multiple large mesoscopic populations, each representing a brain region, coupled through long-range symmetric connections. Rather than assuming random interactions, the coupling matrix is derived from empirical structural connectivity data, with the network size set to approximately 200 nodes, reflecting realistic brain complexity. By applying the linear-noise approximation, which holds in the large-volume limit, we can analytically study the system’s response functions to external perturbations. The presence of intrinsic stochastic fluctuations in the system permits the use of a non-equilibrium version of the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, providing a powerful link between measurable correlations and response functions.

This approach extends previous work that focused on single-population models, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the collective dynamics across the whole brain. Ultimately, our research aims to leverage the generalized fluctuation-dissipation framework to predict and characterize the brain’s response to external stimuli, fostering new insights into brain function and its resilience or susceptibility to perturbations.